A new life: Vida Nueva Women's Cooperative Oaxaca

I had no idea that meeting a group of women weavers in a small dusty town in Oaxaca, Mexico would have such an impact. That I would be so charged and changed by the encounter.

Oaxaca is renowned for its artisan craft, and the town of Teotitlán del Valle in particular for its weaving, so I knew their work would be beautiful, and it is. But more than the aesthetic beauty, or even the integrity of their creative process that blends ancient tradition with their own artistic expression, these women have shown incredible courage and conviction to make a new life for themselves in the face of great challenges, and to transform their community in the process.

To visit Vida Nueva Women’s Cooperative is to be welcomed into the Gutiérrez Reyes family home with humility and generosity. A heavy wooden door opens onto a shaded courtyard shielded from the street by a high wall, overlooked by the two-storey house and cast with dappled light and magenta bougainvillea.

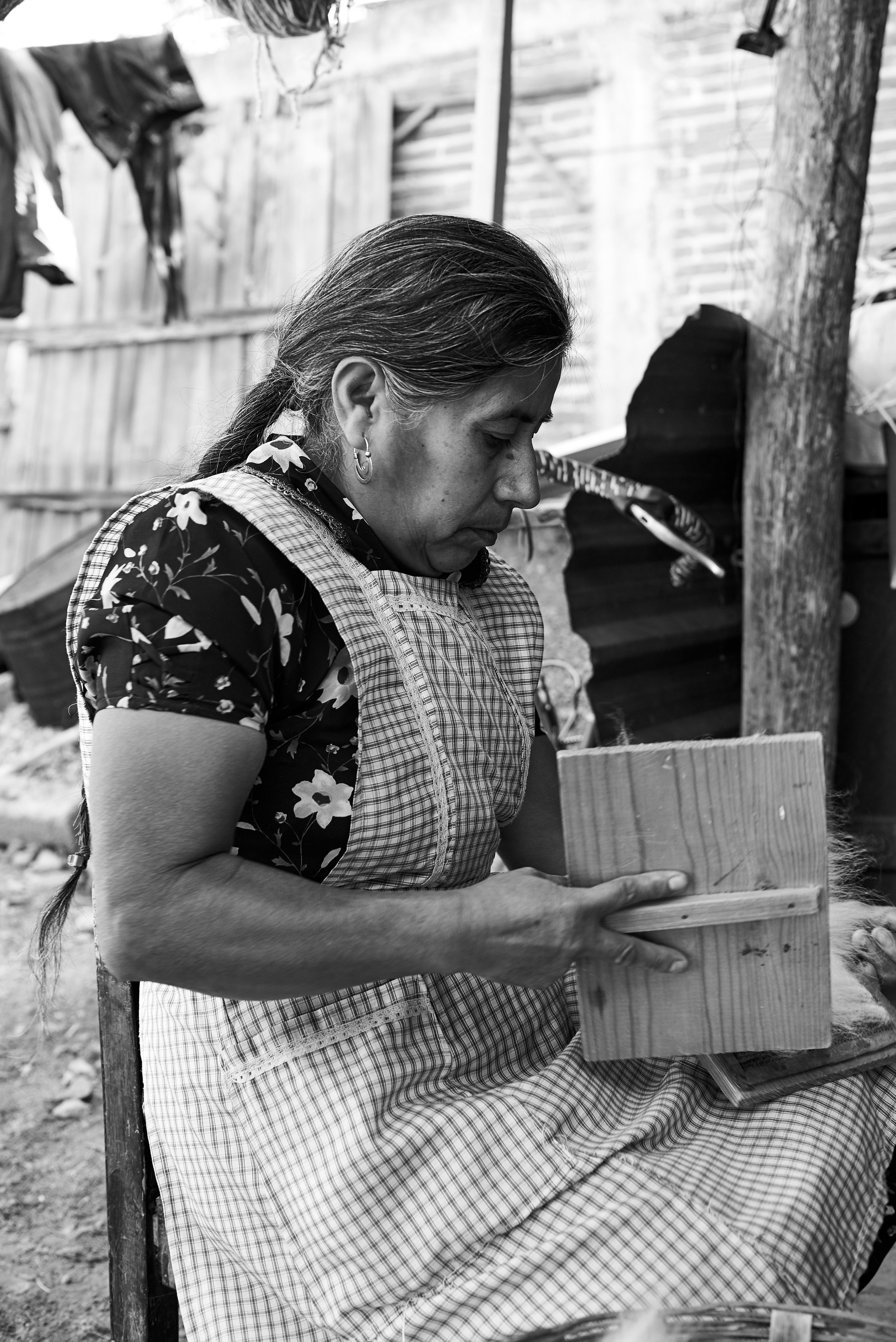

Across the courtyard, there are covered spaces for the workshop where the women wash, card, dye and spin wool which they then weave using pedal looms. There are clotheslines with freshly washed or dyed wool hanging to dry, reaching like telegraph lines across to a covered area displaying materials used for natural pigments, such cochineal (red), pomegranate (mustard) and indigo. Here, their finished work is also shown for sale – brightly coloured rugs and bags hang on walls, with smaller items as such as rebozos and purses placed on tables. And because it is also a home, the family's own washing is on the line too, along with the odds and ends of daily life.

Like the Vida Nueva women, on first impression Teotitlán del Valle seems a quiet, unassuming place. It is a small town of about 6,000 inhabitants approximately 29 kilometres from Oaxaca city and 1,600 metres above sea level. The day we visited, there was little activity on its hot, dusty streets. It felt timeless.

In many ways, Teotitlán is a link to the past. Thought to be founded between 200 BC and 200 AD, it was part of the sophisticated Zapotec civilisation that was once the most prominent in Mesoamerica, reaching its peak when the nearby city of Monte Alban was the cultural, political and economic centre for Oaxaca’s Central Valleys and the south of Mexico between 300 and 600 AD. Teotitlán’s renown for weaving dates back to these times. The community today continue to practice their religious traditions and herbal medicine, pass down legends and language, and maintain their social customs and political structures.

But despite its quiet façade and faithfulness to its heritage, Teotitlán is not a town or a people lost in time. Over the centuries, they have adapted to significant changes - from the fall of Monte Alban to be ruled by the Mixtecs, the Mexica and eventually the Spanish; to the infiltration of capitalism, globalisation and economic migration to the United States.

Vida Nueva Women’s Cooperative is one of the more recent catalysts in its long history of transformation.

When we arrived at Vida Nueva, Pastora, the eldest daughter of the Gutiérrez Reyes family and a co-founder and leader of the cooperative, offered us hot chocolate and a seat in the courtyard while she told us their story.

Pastora explained that the cooperative began in 1994 with a small group of women, including her mother Sofía and grandmother Angelina, who allowed them to use the family home for their meetings and workshop.

It was born out a need for women who were single, widowed or with absent migrant husbands, and had limited opportunities to support their families and meet their obligations to the community through the tithe (cargos) system. Based on the principle of reciprocity (guelaguetza), the cargos system requires the head of each family to make contributions of money and/or to trade goods, and perform their share of community service throughout the year.

This collective ethos is admirable in its ability to unite the community around the common good and to keep alive cultural and religious traditions, but it has also cast a long shadow over women. The complex Zapotec social system has traditionally been controlled by men and structured through a hierarchical, elected system of offices organised and debated via an assembly, to which women were not admitted. Zapotec women have spoken about the multiple forms of discrimination they have experienced as women, indigenous, poor and relatively uneducated or unable to speak Spanish.

With social restrictions on women meeting together alone for more than 30 minutes, the Vida Nueva members began by exploring their ideas secretly while working together at local festivals, whispering while making tortillas.

In the early days, the husbands of the two married women in the cooperative would either come to meetings to observe, sitting with their arms crossed disdainfully across their chests, or they would knock on the door to collect their wives after 30 minutes. The married women soon left the cooperative.

Other men in the town would gossip and call out to the single mothers and widows that they were without a man to control them. But, Pastora countered, there was always someone who encouraged them to keep going. And so, remarkably, they did.

They ventured out into the unknown, intimidating world of the city. As they crossed the main road and boarded the bus to Oaxaca, the younger women held the hands of the elder women who were unaccustomed to wearing shoes or travelling by bus, and did not speak Spanish. With limited education, they did not know how to correctly fill out the government forms to set up their cooperative and felt it was an excuse for the bureaucracy not to help them.

And yet they persisted. They knocked on doors and found a non-governmental organisation that was willing to help. The NGO held workshops with them about how to organise the cooperative as well as gender equality and their rights. They learned how they could make rugs and sell them from their homes instead of through dealers and markets. In doing this, they were able to stay true to their heritage as weavers but also make it their own – incorporating ancient motifs and using natural dyes and methods learned from their elders, while also having the freedom to create their own designs and commericalise their work.

Little by little, they gained more confidence and security. In time, other women joined and they developed their vision and established rotating president and secretary roles. They agreed that their work would be displayed together, promoted equally and sold directly to customers, with the sale of each piece going to the weaver, who then contributes a percentage of her earnings to the cooperative's shared fund. Members are encouraged to seek out opportunities for professional and personal development through attending courses, learning English and even participating in an international congress on the rights of indigenous women in New York.

Pastora explained that as they developed, they realised they had power and authority to make a difference, not just in their own lives but also in their community. Through the cooperative’s shared fund, they complete an annual community project and have delivered workshops in the school and town about issues such as domestic and family violence, drugs and alcohol. Their work has encouraged other women to form their own weaving cooperatives and significantly, they were formally recognised by becoming the first females invited to join the town assembly as leaders of the community.

As I sat listening to Pastora tell their story, I was moved by the tenacity the Vida Nueva women showed to establish their cooperative and thrive in the face of antagonism, while also maintaining such grace, humility and kindness.

What they have achieved is astonishing. On a personal level, they have been empowered to claim economic independence for themselves and their families, allowing them to live creatively and in harmony with nature in their home. And through this, they have effected social change and contributed to the evolution of an ancient culture in modern times, creating new opportunities for the next generations.

Meeting the Vida Nueva women highlighted to me that culture is a choice to practice and shape, not a passive force that will (or should) survive untended. It’s certainly not an easy path to pursue, as their story shows, but it’s such a vital one – for these women, their community, their country and for those of us who have the opportunity to learn from them. Because even though our lives are so different, their story is very much a human one.

When buying a rug that Pastora had made, she explained to me that her design incorporates the ubiquitous maguey leaf, diamonds which represent community and the butterfly which symbolises freedom “because even though we fight for our liberty, we always need more”. Don’t we ever.

Heartfelt thanks to the women of Vida Nueva Women's Cooperative for welcoming us into the Gutiérrez Reyes home and their workshop, sharing their story, and most of all for having the courage and conviction to pursue this path against all the odds. It is truly inspiring.

Thank you also to Andrea Gentl and Martin Hyers and Jessica Chrastil for the introduction and an unforgettable Oaxaca experience.

Since visiting Teotitlán del Valle, I have dived into books such as in La familia Gutiérrez Reyes: Tejedoras de Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca and Zapotec Women: Gender, Class, and Ethnicity in Globalised Oaxaca. I haven’t been able to even begin to do the full story justice here but if you want to learn more, these books are great places to start. And of course, if you have the chance to visit Teotitlán yourself, even better.